We’ve all seen them, and most of us make them. Process lists, to-do lists, lists of all kinds–there’s something very satisfying about checking a little box or crossing an item off a list. However, checklists can serve a greater purpose than as a physical reminder that we’ve accomplished something. In many fields, checklists exist because human brains are fallable and prone to distraction. Pilots use checklists to make sure that amid dozens of relatively simple tasks, none get forgotten. Checklists used before and during surgery reduced the death rate by nearly 50%.

I’ve been doing code review for a long time. In the open source world, code review happens on pretty much any third party contribution. In my time at VMware, pretty much every non-trivial change was expected to be reviewed before checking it in to source control.

In general, people are pretty good at the code review process, but it’s sometimes surprising what can slip through. A natural consequence of the way our brains look at the world is that it’s easy to pay a lot of attention to small details and code style flubs, and completely miss the big picture. It’s for this reason that a lot of designers will start with rough sketches when they start gathering feedback–if something looks too finished, reviewers will only give them comments about the details. Unfortunately, unless you’re starting out with pseudocode or architectural sketches, source code almost always looks “finished” and can therefore encourage some bad habits.

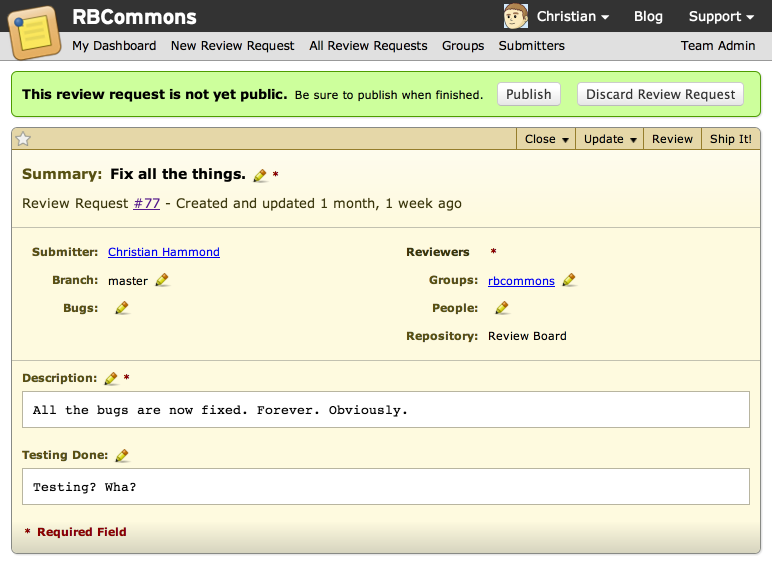

One of the ways that I avoid the pitfall of giving superficial reviews is with checklists. I have a bunch of different sets of checklists that I’ve developed and tweaked over the past few years, and for any given change, I’ll select the sections which apply. I’ve applied some of these at VMware, working on a large desktop application code-base (mostly at the user interface layer), as well as with Review Board itself.

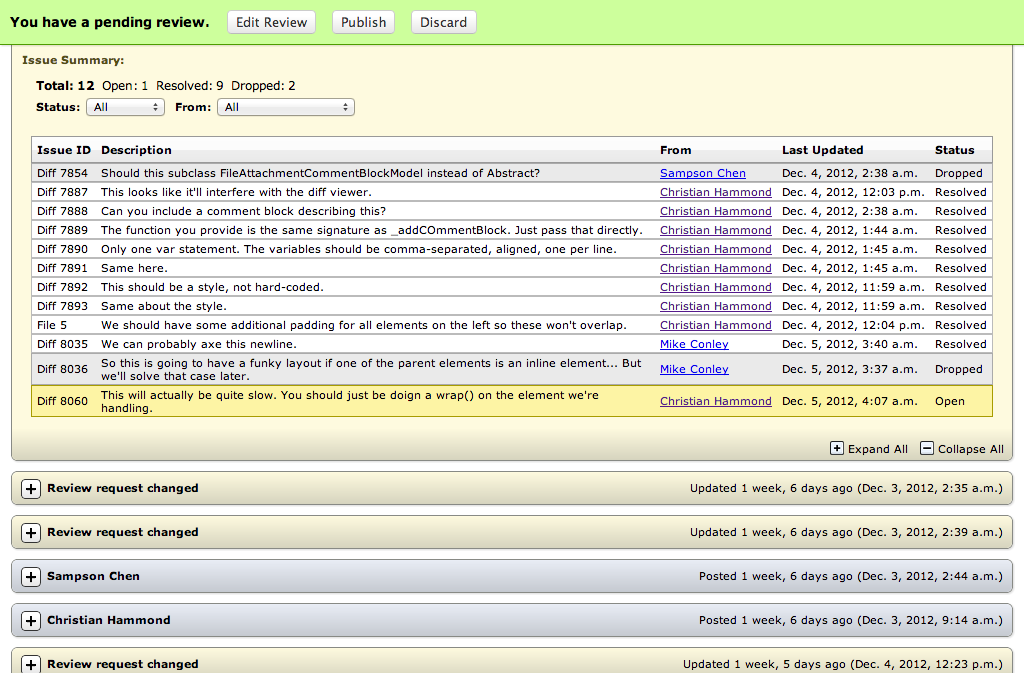

Here are some examples of some of the many checklists I use in my day to day work: